For a few years now, each time Sunita Uike takes a loan, she promises herself it will be the last one. Each time, the weather interferes with her plan.

When she borrowed ₹30,000 from a private microfinance company last year, just before the sowing season in June, she was confident she would get enough work as a farm labourer to repay the monthly instalment of ₹1,840. But the rains got delayed and for days on end, Uike didn’t get any work.

As the sole breadwinner of her family in Umri village in Maharashtra’s Wardha district, with two children and a husband to feed, Uike, unable to pay up, borrowed ₹30,000 again. As the farming season progressed, her hopes of being able to eke out a living, enough to pay off her instalments, were bolstered. But a month later, the region was lashed by rains so heavy it washed away all the farms in and around the village.

Sunita Uike works as a farm labourer in Umri village in Maharashtra’s Wardha district.

| Photo Credit:

Kunal Purohit

Nearly 800,000 hectares across the State were damaged. With farm owners reeling under severe losses, Uike found herself out of work once more and in heavy debt. Yet again, she borrowed ₹40,000 from another microfinance company, in part to pay off old loans and to simply survive.

Across the village, nearly every woman has a number — many have taken two loans, others three. Some, like her friend, Neelima Kusre, have as many as six. The debt, often, comes at interest rates as high as 30%, and with coercive repayment tactics.

Men mostly debt-free

Uike, who still has a debt of ₹1,00,000, says microfinance has caused a tectonic shift in society — men are now debt free and women are saddled in heavy debts. “Our men don’t have any loans anymore, maybe just a crop loan from a co-operative bank, nothing else. In contrast, the women are carrying massive loans around their necks,” she says.

Microfinance, defined by the Reserve Bank of India as collateral-free loans given to low-income households earning up to ₹3,00,000 annually, was meant to create “microentrepreneurs”, according to the World Bank, by helping them access credit for their businesses to grow.

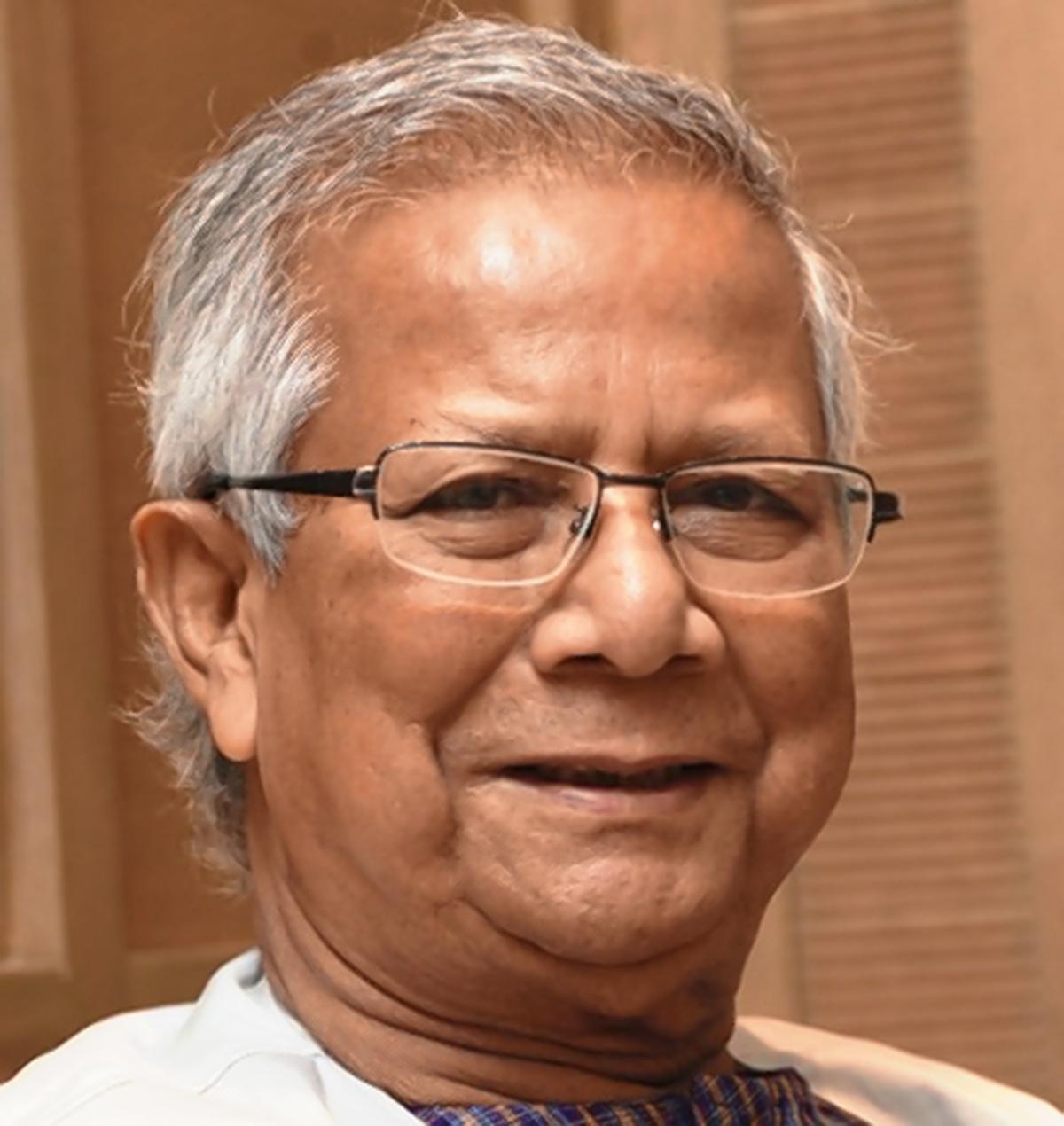

Nobel Peace Prize awardee and social entrepreneur Muhammad Yunus is widely credited to have invented the modern-day version of microfinance after his experiments in rural Bangladesh in the 1970s. In 1983, he founded the Grameen Bank and the practice of microfinance was institutionalised. Yunus is said to have offered a $27 (approx. ₹240) loan to artisans and farmers in rural Bangladesh who were unable to access credit from banks. Instead, Yunus created a model of distributing small loans to a group of borrowers who could act as co-guarantors.

In Vidarbha, the epicentre of India’s agrarian crisis with thousands of farmers dying by suicide over the last two decades, changing weather patterns and easy access to microfinance loans are creating a new crisis: pushing women farmers into an unending spiral of debt and despair. Figures with the Microfinance Institutions Network (MFIN), an industry association, show that the number of microfinance loans in Maharashtra rose from 82.89 lakh on March 31, 2021 to 91.66 lakh on March 31, 2022.

While thousands of mostly male farmers in the region have been reported to commit suicide annually, local activists suspect that unsustainable debts might even be pushing some women over the edge. But government data is unlikely to reflect this as farmer deaths by suicide are not segregated by gender, says the Maharashtra government’s Revenue and Forest department in response to an RTI plea.

The crisis is not restricted to Maharashtra. The agrarian State of Punjab has also reported its women being burdened with unending cycles of microfinance loans. As of September 30, 2020, the number of women borrowers in Punjab stood at 12.88 lakh with an outstanding principal amount of ₹4,387 crore, according to a statement from MFIN.

In Tamil Nadu, a survey by the All India Democratic Women’s Association in December 2021 revealed women were increasingly turning to microfinance loans and enduring abuse and ill-treatment at the hands of loan agents when unable to repay.

THE MACRO PICTURE

Number of microfinance borrowers: 6.4cr

Number of loan accounts: 12.6 cr

State-wise figures: Loans disbursed (as on December 31, 2022)

Bihar: ₹43,381 cr

TamilNadu: ₹42,529 cr

West Bengal: ₹32,598 cr

Uttar Pradesh: ₹29,282 cr

Karnataka: ₹28,399 cr

Maharashtra: ₹24,896 cr

(Source: MicroMeter by MFIN)

Rapidly-growing industry

March 2013: ₹21,245 cr

March 2019: ₹179,314 cr

March 2020: ₹231,788 cr

March 2021: ₹259,377 cr

March 2022: ₹285,441 cr

(Source: India MicroFinance Review, 2021-22)

Loans for weddings, household expenses, school fees…

When she borrowed money, Uike told the lending company that she was going to buy goats. In reality, “women take loans to buy things for the household, for farming, for daily expenses, for weddings at home, for their children’s education”, says Madhuri Khadse, head of Prerna Gram Vikas Sanstha, a not-for-profit based in neighbouring Yavatmal district, working on issues of women farmers.

Madhuri Khadse, head of Prerna Gram Vikas Sanstha, a not-for-profit based in Yavatmal district, working on issues of women farmers.

| Photo Credit:

Kunal Purohit

In Yavatmal, 35-year-old Savita Bhiwalkar, an Anganwadi worker, earns ₹2,200 a month. But her instalments for the two loans she has taken for ₹80,000 add up to ₹4,700 each month. To make up for the deficit, Bhiwalkar labours on the farms of villagers for ₹150 a day. But most of last year was a washout, with weather disruptions. “It has been a very difficult year,” Bhiwalkar says. “In a season, there is only a limited window of work for farm labourers like me. But when there is excess rainfall and flooding, even that window reduces.”

Savita Bhiwalkar, an Anganwadi worker in Yavatmal.

| Photo Credit:

Kunal Purohit

However, Alok Misra, CEO and Director of MFIN, says that multiple loans are not a sign of rising indebtedness. “The RBI’s indebtedness cap also ensures that the total annual debt repayment does not exceed 50% of their annual income. Hence, even if they have multiple loans, the total repayment cannot exceed 50% and this ensures they are not indebted,” he says.

Misra’s words don’t ring true on ground. Thanks to the way the loans are designed and the tactics employed to recover them, skipping repayment is not an option.

Loans are given to individuals within a self-constituted group of 5-10 women — friends, family members, neighbours. The instalments can be weekly, fortnightly, or monthly, and collection takes place with loan agents holding meetings with the group on the due date.

“When one member does not pay up, the loan agent pressurises all the others in the group so that they tell her to pay up and if that member cannot, then they shell out her contribution,” says Uike. For many women, not being able to repay an instalment results in a double-whammy of facing possible societal censure and anger as well as abusive microfinance officials.

“Agents come to your house, they insult you, call you names, even if you are late in repaying the instalment by a couple of hours,” she says.

A farm in Maharashtra’s Wardha district.

| Photo Credit:

Kunal Purohit

No fixed wages

Her closest friend, 37-year-old Maya Siram, has suffered this fate numerous times. One time, Siram, who has over four pending loans worth ₹1,20,000, missed her instalment because she had been sick. When the agent came home to demand the instalment and answers, Siram explained her state. As a daily-wage worker with no fixed wage, sick days mean no income. Her husband, too, earns daily wages.

“I told him, we had no money to eat, leave alone pay back the loan. But he refused to leave my house,” she says. “Finally, I asked him, ‘Should I kill myself? Will that satisfy you?’ He heard that and left.”

The next time, though, Siram was not so lucky. Farm work had dried up in the village. On a Saturday morning, when her instalment of ₹970 was due, Siram set out for the nearby town of Arvi to look for work, as a desperate, last-minute dash. When she reached the town, her phone started ringing incessantly — the loan agent was in her village, looking for her. She tried to buy time, still wandering through the market, asking for a job. But the calls continued. “The agent went to my house and called me to say, he wouldn’t leave unless I paid my instalment,” she says.

Siram grew desperate. The phone didn’t stop ringing. She realised there was only one way she could end her misery — she pawned her phone for ₹3,000 and asked the shop-owner to transfer the ₹970 straight to the agent at her house, so that he would leave. After repaying her loans, when she went back to get her phone a month later, the shop owner charged her ₹300, or 10%, as interest.

Mounting crisis

In States like Punjab, rising agrarian distress and indebtedness have pushed women borrowers to take their own lives as per news reports. In neighbouring Sri Lanka, microfinance loans have caused widespread turmoil with many debtors committing suicide, and political parties promising to ban this form of credit. In 2010, over 200 people in Andhra Pradesh, heavily in debt thanks to microfinance loans, died by suicide after they were hounded by debt collectors.

Calamity insurance

In India, the Reserve Bank of India last year issued regulatory directions for the microfinance industry and lifted the cap on interest rates, but asked microfinance companies not to charge “usurious” interest rates from borrowers. The RBI’s chief general manager in the department of communication, Yogesh Dayal, did not respond to a message and an email sent to him.

MFIN’s Misra says the industry is aware of the disruptions that weather upheavals are causing in repayment of loans. “To deal with this, MFIN has already piloted a national calamity insurance, to be followed by full rollout after regulatory approval. Such an insurance will mean that if there is a flood or excess rainfall breaching the pre-decided threshold certified by remote data sensing measurement, then the insurance will take care of at least three to four repayments for the borrowers,” Misra says.

Till then, Uike, eager to cultivate her one acre, has promised herself, yet again, not to borrow any more.

The writer is a Mumbai-based independent journalist, and author of an upcoming book on Hindu nationalism.