If being vegetarian means having diets loaded with dal (pulses), sabzi (vegetables) and phal (fruits), sans any animal-origin products, India would probably not make the cut.

The latest official Survey on Household Consumption Expenditure for 2022-23 (August-July) shows that the average monthly per capita spending in rural India on vegetables (at Rs 202.86), fresh and dry fruits (Rs 140.16) and pulses (Rs 75.98) was lower than on milk and milk products (Rs 314.22). The value of per capita consumption was similarly higher for milk (Rs 466.01) than vegetables (Rs 245.37), fruits (Rs 245.73) and pulses (Rs 89.99) even in urban India.

No less revealing is the per capita expenditure on dal, sabzi and phal in “vegetarian” Rajasthan being below the national average (both rural and urban) for these items. Or, for that matter, the value of vegetable consumption by the average person in the eight Northeast Indian states being higher than not just the corresponding all-India level, but even of “Vaishnav-Jain” Gujarat.

Milk’s the difference

Simply put, being vegetarian in India is not being vegan. Indians, if at all, are lacto-vegetarian. Even those who call themselves vegetarian generally don’t abstain from consuming milk and dairy products.

In a monograph titled Key to Health – originally penned in 1942, while he was incarcerated at Pune’s Aga Khan Palace – Mahatma Gandhi made a distinction between “vegetarian” and “flesh” foods. The latter included fowl and fish. Milk, for him, was an “animal food”, like “sterile eggs” that are laid by hens (without being “allowed to see the cock”) and do not develop into chicks.

“Milk is an animal product and cannot by any means be included in a strictly vegetarian diet…But experience has taught me that in order to keep perfectly fit, vegetarian diet must include milk and milk products such as curd, butter, ghee, etc.,” he wrote, while hoping for the discovery by selfless scientists of a “vegetable substitute” that would obviate the “necessity of adding milk to [a] strict vegetarian diet”.

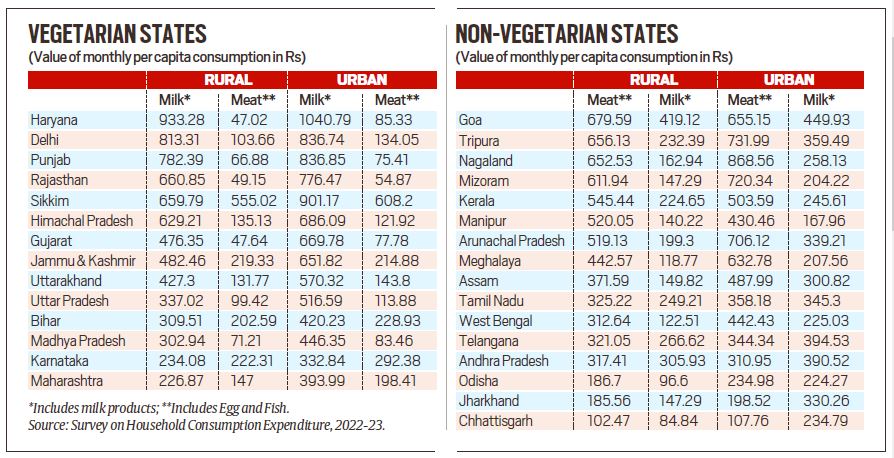

The monthly per capita consumption expenditure on vegetables may be relatively low or even below the all-India average in Gujarat and Rajasthan. But the average rural Gujarati spends Rs 476.35 and her urban counterpart Rs 669.78 per month on milk, with these at Rs 660.85 and Rs 776.47 respectively for Rajasthan. The value of the per capita milk consumption in the two states is way above the corresponding average of Rs 314.22 for rural India and Rs 466.01 for urban India.

There is, perhaps, some nutritional underpinning to milk consumption being high among vegetarians in India. Animal products, including milk, are rich sources of protein. These contain a balanced combination of all essential amino acids that the human body cannot synthesise and have to, therefore, be supplied through one’s diet. Plant proteins, by contrast, are incomplete. Even soyabean, pulses and legumes are deficient in the essential amino acids, methionine and cysteine.

What it means is that the pure vegan route requires a variety of plant protein sources, used in the right combination, to achieve the desired amino acid balance. An easier, more practical, alternative is to be lacto-vegetarian. Not for nothing that milk has traditionally been synonymous with purity and good health in India – even in regions or among communities steeped in anti-meat values,.

Which are the “vegetarian” and “non-vegetarian” states?

The accompanying tables show that the states where the average household monthly per capita expenditure on milk and dairy products is higher than on egg, fish and meat – in other words, “vegetarian” – are primarily in North, West and Central India.

These cover the Vaishnav-Jain-Arya Samaj belt of Gujarat, Rajasthan, Haryana and Punjab, the Hindi heartland of Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh and Bihar, and, to a lesser extent, Maharashtra and Karnataka.

In all, there are some 14 “vegetarian” states. That includes Sikkim, although the average person’s monthly spend on egg, fish and meat there (Rs 555.02 in rural and Rs 608.20 in urban) is much above the corresponding all-India numbers of Rs 185.16 and Rs 230.66 respectively.

At the other end are the “non-vegetarian” states. There are 16 of them, whose average consumption expenditure on egg, fish and meat exceeds that on milk, at least in rural areas.

These include not only the hardcore fish and meat (even beef) eating states such as Kerala, Goa, West Bengal and those in the Northeast. Equally interesting are Odisha, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh – states with significant tribal populations that is reflected in their high per capita consumption of egg, fish and meat relative to milk, especially in rural areas. Rural households in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, likewise, exhibit a preference for what Indians normally view as “non-vegetarian” items.

The defining factor of “vegetarian” in India appears to be not dal-sabzi-phal, but doodh or milk. Those who have a lot of it tend to abhor flesh foods. Nutritionally too, so long as they drink doodh, they miss little by not eating fish, meat or egg.